PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK [1975 / 2014] [The Criterion Collection] [DVD] [USA Release]

The St. Valentine’s Day Mysterious Picnic at Hanging Rock!

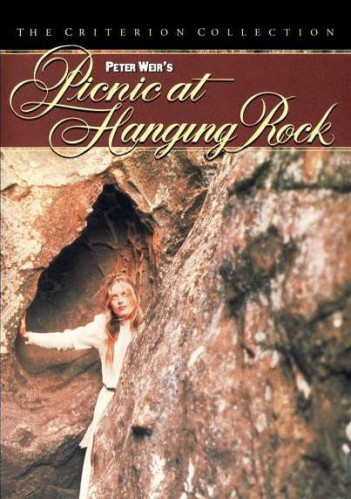

Twenty years after it swept Australia into the international film spotlight, Peter Weir's stunning 1975 masterpiece remains as ineffable as the unanswerable mystery at its core. A Valentine's Day picnic at an ancient volcanic outcropping turns to disaster for the residents of Mrs. Appleyard's school when a few young girls inexplicably vanish on Hanging Rock. A lyrical, meditative film charged with suppressed longings, ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ is at long last available in a pristine widescreen director's cut with a newly-minted Dolby® digital 5.1 channel soundtrack.

The Criterion Collection is dedicated to gathering the greatest films from around the world and publishing them in editions of the highest technical quality. With supplemental features that enhance the appreciation of the art of film.

FILM FACT No.1: Awards and Nominations: 1976 Australian Film Institute: Nomination: AFI Award for Best Film for Hal McElroy, Jim McElroy and Patricia Lovell. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Direction for Peter Weir. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Original Screenplay or Adapted for Cliff Green. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Achievement in Cinematography for Russell Boyd. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Actress in a Lead Role for Helen Morse. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Tony Llewellyn-Jones. Nomination: AFI Award for Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Anne-Louise Lambert. 1976 Australian Writers' Guild: Win: Awgie Award for Feature Film for Cliff Green. 1976 British Society of Cinematographers: Nomination: Best Cinematography Award for Russell Boyd. 1976 Faro Island Film Festival: Nomination: Golden Moon Award for Best Film for Peter Weir. 1976 Taormina International Film Festival: Win: Golden Charybdis for Peter Weir. 1977 BAFTA Awards: Win: BAFTA Film Award for Best Cinematography for Russell Boyd. Nominations: BAFTA Film Award: Best Costume Design for Judith Dorsman. Nominations: Best Sound Track for Don Connolly and Greg Bell. 1979 Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA: Win: Saturn Award for Best Cinematography for Russell Boyd. Nomination: Saturn Award for Best Writing for Cliff Green.

FILM FACT No.2: The novel was published in 1967. Reading it four years later, Patricia Lovell thought it would make a great film. Patricia Lovell did not originally think of producing it herself until Phillip Adams suggested to Patricia Lovell try it; and s Patricia Lovell optioned the film rights in 1973, paying $100 for three months. Patricia Lovell hired Peter Weir to direct on the basis of his film ‘Homesdale,’ and Peter Weir brought in Producers Hal McElroy and James "Jim" McElroy to help produce. Screenwriter David Williamson originally was chosen to adapt the film, but was unavailable and recommended noted TV writer Cliff Green. Joan Lindsay had approval over who did the adaptation and she gave it to Cliff Green, whose first draft Patricia Lovell says was “excellent.” The finalised budget was A$440,000, coming from the Australian Film Development Corporation, British Empire Films and the South Australian Film Corporation. $3,000 came from private investors. Filming began in February 1975 with principal photography taking six weeks. Locations included Hanging Rock in Victoria, Martindale Hall near Mintaro in rural South Australia, and at the studio of the South Australian Film Corporation in Adelaide. To achieve the look of an Impressionist painting for the film, director Weir and director of cinematography Russell Boyd were inspired by the work of British photographer and film director David Hamilton, who had draped different types of veils over his camera lens to produce diffused and soft-focus images. Russell Boyd created the ethereal, dreamy look of many scenes by placing simple bridal veil fabric of various thicknesses over his camera lens. The film was edited by Max Lemon.

Cast: Rachel Roberts, Vivean Gray, Helen Morse, Kirsty Child, Anthony Llewellyn-Jones, Jacki Weaver, Frank Gunnell, Anne-Louise Lambert, Karen Robson, Jane Vallis, Christine Schuler, Margaret Nelson, Ingrid Mason, Jenny Lovell, Janet Murray, Vivienne Graves, Angela Bencini, Melinda Cardwell, Annabel Powrie, Amanda White, Lindy O'Connell, Verity Smith, Deborah Mullins, Sue Jamieson, Bernadette Bencini, Barbara Lloyd, Wyn Roberts, Kay Taylor, Garry McDonald, Martin Vaughan, John Fegan, Peter Collingwood, Olga Dickie, Dominic Guard, John Jarratt, Kevin Gebert (uncredited) and Faith Kleinig (uncredited)

Director: Peter Weir

Producers: A. John Graves, Hal McElroy, Jim McElroy and Patricia Lovell

Screenplay: Joan Lindsay (novel) and Cliff Green (screenplay)

Composers: Bruce Smeaton and Gheorghe Zamfir

Costume Design and Wardrobe Department: Judith Dorsman (costume designer), Mandy Smith (wardrobe assistant) and Wendy Stites (associate costume designer)

Cinematography: Russell Stewart Boyd, A.O., A.C.S., A.S.C., (Director of Photography)

Image Resolution: 1080i (Eastmancolor)

Aspect Ratio: 1.66:1

Audio: English: 5.1 Dolby Digital Audio

Subtitles: English

Running Time: 107 minutes

Region: NTSC

Number of discs: 1

Studio: B.E.F. Film Distributors PTY Ltd / The South Australian Film Corporation / The Australian Film Commission / JANUS FILMS / The Criterion Collection

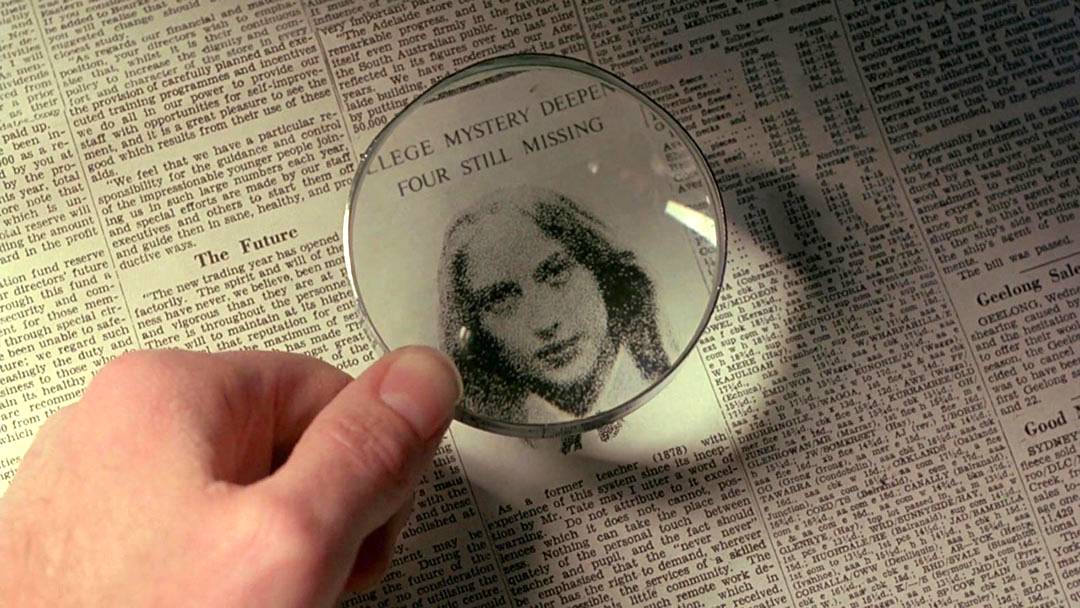

Andrew’s DVD Review: In the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ [1975] it is on the morning of Saint Valentine’s Day, one Saturday in 1900, the schoolgirls boarding at Appleyard College near the small Australian town of Woodend, Victoria prepare for a day picnicking at Hanging Rock. In raptures they recite poetry from the Valentine’s cards they have presumably sent one another; they put on their muslin dresses, and in a cross between a balletic embrace and an evolutionary procession, they awkwardly help each other with their corsets; and then they are off, not before a word from the stern headmistress Mrs. Appleyard [Rachel Roberts], who warns them against wandering and of the dangers of the Australian wildlife, reminding them that although it is warm, for the sake of modesty they must wait until they are beyond the town before removing their gloves. Mrs. Appleyard expects the girls back in time for a light supper, but at the rock three of them vanish as if into thin air.

One girl, Sara Waybourne [Margaret Nelson], in punishment for something undisclosed, is not allowed to attend the picnic, and Sara Waybourne waves to her friend Miranda St Clare [Anne-Louise Lambert] from the balustrade atop the schoolhouse. Already there is a faint disquiet over the school, the headmistress, and the schoolgirls themselves, sun-dappled and romantic, depicted dreamily and gauzily atop sinuous panpipes. They are overripe, and there is a precarious balance between the girls as they sit primly in the back of the carriage and the schoolboys who chase through the town in their wake; between the cosseted elegance of the girls and the working town; between the two young men who haggle over alcohol in the vicinity of the picnic; between the Valentine’s cake which Miranda St Clare cuts in half, plunging the knife, and the ground beneath teeming with bugs. Meanwhile the rock hums.

Certainly there are angles: have the girls simply fallen into the bush, should we suspect Michael Fitzhubert [Dominic Guard], the young Englishman who follows someway after the girls, straying from his lunch with his uncle and aunt, or perhaps even the mathematics teacher Miss Greta McCraw [Vivean Gray], who we discover followed the girls deep into the rock wearing just her undergarments? Later in the film we might also come to suspect Mrs. Appleyard, whose sternness with Sara Waybourne [Margaret Nelson] turns into something more sinister while she struggles with fees in the face of a crumbling school. Yet it’s hard to escape the impression that the girls’ absence is indefinable, something simply beyond our grasp. Each step they take up and into the rock, buttressed by pipes, choral chants, classical music and ancestral rumbling, while lizards creep and flocks of birds fly overhead, is at once an epiphany, rhythmic and transgressive and brimming with portent.

About a week after the picnic, Irma Leopold [Karen Robson] is found by Albert Crundall [John Jarratt], the Fitzhuberts’ coachman, thanks to a clue provided by Michael Fitzhubert [Dominic Guard] who has spent day and night searching the rock: in the novel by Joan Lindsay from which the film was adapted, the clue is a scrawled note, but here it is a piece of lace torn from one of the girls’ dresses. Irma Leopold [Karen Robson] hands and nails are ripped and broken, her head is bruised, but she is “intact” and has no marks on her feet, inexplicable since she was found wearing neither stockings nor shoes.

In one of the film’s blunter gestures, the portly Edith Horton [Christine Schuler] who lags behind the other three is portrayed as more earthbound and Edith Horton bows her head to the dirt as the others gaze at the rock face, and when they disappear Edith Horton runs back down with a piercing scream. Nobody can really elucidate what happened, or quite recall the sequence of the day’s events. Two watches stopped at twelve. Bugs threatened to infest the picnic. Lizards roamed and birds flew but the girls wilted in the heat, and fell dazed or asleep.

The film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ develops at a slow pace, letting the viewer really enjoy Russell Stewart Boyd’s beautiful cinematography. One may argue that it doesn’t take a lot of talent to make Australia’s landscapes gorgeous, but this Oscar-winning cinematographer’s craft lies in giving a scary, unfriendly feel to what is naturally beautiful. And the rich, warm colours will make anyone nostalgic for a time when cinema wasn’t dominated by washed out, teal and orange hues.

In fact each scene in ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ is not only carefully composed, but sometimes framed and suspended like an Impressionist painting: of the rock itself, or of the girls in slumber. Director Peter Weir and Cinematographer Russell Stewart Boyd, drawing from the experiments of photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson, draped bridal veil over the camera lens to produce the film’s diaphanous soft-focus. Its cadenced throngs also evoke the Renaissance, and Mme de Poitiers in one of the film’s resonant lines says “I know that Miranda St Clare is a Botticelli angel.” No doubt some people find ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ meandering and self-indulgent, perhaps better to say self-absorbed. Through the thick air that hangs over the movie, stilted and enclosed, we sense that even more than the picture itself, the girls are not going to bend to our whims much less disclose their secrets.

‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ is faithfully adapted from Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel of the same name, telling the story of a fateful St. Valentine’s Day in central Victoria in 1900. Four students from Appleyard College, Educational Establishment for Young Ladies — the ethereal Miranda St Clare, the beautiful Irma Leopold, whip-smart Marion Quade, and pesky, whining Edith Horton — depart from their classmates and teachers to penetrate more deeply the lush mysteries of Hanging Rock, a foreboding volcanic mass that, their headmistress, Mrs. Appleyard, warns them, is both a “geological marvel and . . . extremely dangerous.”

Only Edith Horton returns, gripped in a fit of screaming hysteria and unable to recall what has transpired. In the confusion, Miss McCraw, the middle-aged math teacher, vanishes as well. Several days later, Irma is found alive but remembers nothing of her experience. Miranda St Clare, Marion Quade, and Miss McCraw are never seen again, and a series of torments and major and minor tragedies wait nearly all involved.

With its Victorian hothouse atmosphere and fetishism (from the gloves and stockings to the flowers the girls fondle to the fixation on corsets) and its focus on the burgeoning sexual curiosity of the girls and the women, making ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ a deliciously ripe for Sigmund Freud or Jungian therapy interpretation — and while the novel plays it cool, more interested in social mores and their unravelling, the movie is all heat. Director Peter Weir focuses on the sensate, the pleasures and dangers made flesh, repeatedly using his camera to pull back every curtain, to lift every petticoat, to unfurl every corset.

Reading the film this way, one can see the bolder girls, aroused by the pagan pleasures of passing valentines and, in far deeper registers, by the wildness and eruptive lore associated with Hanging Rock, as eager to pass through innocence and into adult sexuality. It is a great and perilous passage to a place that they long to go (others, like Edith Horton, fear to go, are not equipped to go), but from which there can be no return. To make the journey, the film hints, and one must need to leave behind the same-sex passions of adolescence: as Miranda St. Clare gently warns her devoted roommate Sara Waybourne, “You must learn to love someone apart from me, Sara Waybourne. I won’t be here for very much longer.”

While Sara Waybourne later takes this warning as evidence of Miranda St. Clare’s foreknowledge, it directly follows Miranda St. Clare’s invitation to Sara Waybourne to join her on a family visit one day, suggesting she doesn’t plan on literally leaving but on “leaving” the safety of their intense school friendship for something else, something that is never named — perhaps a kind of sublime. Eyes fixed on the rock, expression serene and ready, Miranda St. Clare is ready.

“Miranda knows lots of things other people don’t know,” Sara says after the disappearance. And that is how ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ can come to feel to the viewer. Just as everyone in the film is tortured by the not knowing, so too is the audience. By not providing a “solution,” the film leaves us face-to-face with our own self-generated projections, our shameful fantasies. Any dark, unseemly, or erotic scenario we imagine in our heads, we must acknowledge as our own. The movie, the story, Miranda St. Clare herself won’t take it back. It is ours, and we must claim it.

Nearly forty years later, it is almost impossible to encounter director Peter Weir’s ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ without always already knowing about its supposed non-ending, which, for many, may remove the possibility of frustration. That frustration, however — the unsettling, provocative sense of hidden truths withheld from us — is integral to the film itself, and one of its greatest powers.

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK MUSIC TRACK LIST

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, 2nd Movement (Written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart)

Piano Concerto No 5 in E Flat Major (Emperor Concerto), 2nd Movement (Written by Ludwig van Beethoven)

Doina: Sus Pe Culmea Dealului (Written by Gheorghe Zamfir) [Performed by Gheorghe Zamfir]

Doina Lui Petru Unc (Written by Gheorghe Zamfir) [Performed by Gheorghe Zamfir]

Prelude No 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier (Written by Johann Sebastian Bach)

String Quartet in No 1 in D Major, 2nd Movement (Written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky)

PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK (The Ascent Music) (Written by Bruce Smeaton)

* * * * *

DVD Image Quality – JANUS FIMS and The Criterion Collection presents the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ with a very impressive improved 1080i image quality and is also shown in the director Peter Weir’s preferred aspect ratio 1.66:1. This new digital transfer was created on a high-definition Spirit Datacine from a new 35mm interpositive made from the original negative and was supervised personally with director Peter Weir and the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ gets a much needed upgrade from Criterion, who present it in a new dual-format special edition. The DVD delivers the film with a new 1080i high-definition digital transfer on a dual-layer disc and delivers a standard-definition anamorphic transfer on the first dual-layer DVD and also the shorter director's cut of the film. The DVD's transfer also looks fairly good, but again the general limitations of the format mar it slightly. Detail isn't as rich, with textures on fabrics or the rock face not coming through as clearly, and compression is more of an issue. But for a DVD transfer it looks nice. The source is also far better, with only a few minor marks and scratches remaining, all of which are few and far between. In the end the wait was more than likely unnecessarily long, but it was more than worth it as we get a substantially cleaner image that looks incredibly film-like. Please Note: As to director Peter Weir wanting the film in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and personally I found this totally weird and not at all to my liking, to me personally, it looks more like 1.37:1 aspect ratio film.

DVD Audio Quality – JANUS FIM and The Criterion Collection brings us the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ a sound that was created from a newly-minted 5.1 Dolby Digital Audio channel soundtrack that was supervised personally with the help of director Peter Weir. The surround sounds work more to serve the film's fairly haunting music score, which spreads out in creating a very ethereal feel. Dialogue stays mostly to the front speakers, and is clear and articulate. Depth and range is nice, but the audio track isn't overly aggressive, remaining low-key and subtle most of the time, just like the film. All in all, it was a most joyous audio experience for a film of this top class quality.

* * * * *

DVD Special Features and Extras:

Remastered high-definition digital film transfer, supervised by director Peter Weir, and especially the 5.1 Dolby Digital Audio soundtrack on this The Criterion Collection DVD

Special Feature: Theatrical Trailer [1975] [480i] [1.66:1] [4:49] This is the Original Theatrical Trailer for the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK.’

BONUS: You have a 4 page in-depth 1979 liner notes on the film ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ by Vincent Canby. Vincent Canby (27th July, 1924 – 15th October, 2000) was an American film and theatre critic who served as the chief film critic for The New York Times from 1969 until the early 1990’s, and then its chief theatre critic from 1994 until his death in 2000. Vincent Canby reviewed more than one thousand films during his tenure for The New York Times.

Finally, Peter Weir's landmark ‘PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK’ is still a tough nut to crack. First-time viewers will be drawn in and pushed away in equal measure by the film's hypnotic visuals and undercooked mystery elements, yet the final product remains more than the sum of its parts. Director Peter Weir would go on to direct more accessible fare like ‘Witness,’ ‘Dead Poets Society,’ ‘The Truman Show’ and ‘Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.’ But anyone with a soft spot for dreamlike, late Victorian-era visuals will have no problems jumping right in. Long-time followers of the film should be enormously pleased with The Criterion Collection's new “Dual-Format” package. Recommended!

Andrew C. Miller – Your Ultimate No.1 Film Aficionado

Le Cinema Paradiso

United Kingdom